We owe our past and future existence on Earth to fungi. Some can heal you, some can kill you, and some can change you forever. And the people who love them are convinced that mushrooms explain the world.

Anne Strainchamps (00:13):

And It's To The Best Of Our Knowledge. What if I told you that you owe your existence to a mushroom?

Lawrence Millman (00:27):

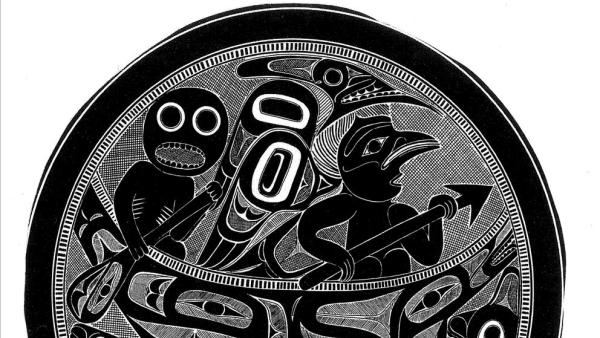

Oh, yes. Fungus man. Fungus man is very interesting. He's the personification of a large bracket fungus.

Anne Strainchamps (00:42):

Lawrence Millman with a story from way back in the mists of time.

Lawrence Millman (00:50):

Fungus man was a friend of Raven who created the world. Raven created man but then scratched his head. What do I do next? There doesn't seem to be any more of the species I've just created but fungus man was quite smart. He told Raven, I can take you in my canoe to the island where female genitalia scamper around. And they arrive on this island and there are all these female genitalia scampering over the rocks. The description in the myth makes them look a little bit like tightened shell. So Raven is really happy. He collects a lot of them and takes them back and fixes them to the man. They therefore become women and then the man who don't have them fixed to themselves, look very happily at the men who do or now women. As the old man who told me this story said, if it wasn't for fungus man, I wouldn't be telling you this story. And you wouldn't be here to listen to it.

Anne Strainchamps (02:51):

There's a lot of truth buried in this. I'm Anne Strainchamps. This one is from the height of First Nation people in British Columbia and the truth we do owe our past and maybe future existence on earth to the kingdom of mushrooms. Fungi.

Paul Stamets (03:14):

Let's go back in time. Most people may not realize that we shared a common interest with fungi 650 million years ago.

Anne Strainchamps (03:23):

My college mycologist Paul Stamets.

Paul Stamets (03:29):

Fungi with our first organisms to come to land. As they grow, they lead the path and then plants came to land several hundred million years after fungi. Now we go back to 250 million years ago, we had a great cataclysmic event. Enormous amounts of debris were jettisoned to the atmosphere. Sunlight was choked off probably for decades. We don't know how long. A massive extinction, most plants and animals became extinct and fungi inherited the earth. And those organs that paired with fungi survived. And this is a lesson that we need to learn. We are now in six X, the sixth greatest extinction event known in the history of life on this planet. We pair with fungi. We will hopefully survive this extinction event.

Anne Strainchamps (04:24):

Can mushroom save the world. Let's find out. First of all, can I just say other than when I'm cooking, I don't really think about mushrooms all that much, but then Steve Paulson started talking about Paul Stamets. This has to be the most passionate mycologist on the planet. Paul is an evangelist for the healing power of mushrooms. He spends his time roaming old growth forests in the Pacific Northwest looking for rare species. And he works with the U.S. Defense Department and the NIH to develop new technologies and new medicines from mushrooms. For example.

Paul Stamets (05:12):

Well, of course, everyone knows about penicillin that came from a mold, but many of the mushroom producing fungi are very strongly active against bacteria including meso staph, including E. coli. And I'm doing research against mycobacterium tuberculosum. One of our fungi from the old growth forest, which is called agarikon shows to be highly active against orthopoxes including smallpox. And so I'm as much of my resources and attention has been focused on getting as many strains of this old growth fungus in culture as possible because it's rapidly on the decline. And as the pollution and the forests are cut back, we're losing what I call microdiversity. And it's very important that we preserve some of these ancestral strains before they become extinct.

Steve Paulson (05:59):

So tell me how this would work. I mean, suppose there was an outbreak of smallpox, how might this particular fungus be used as a remedy?

Paul Stamets (06:07):

So what's unique about this fungus. It used to grow in Europe and is now practically extinct. The ancient name is called agarikon but the Greek name for it was elixirium ad longam vitam. The elixir of long life. And Dioscorides first published it in 65 AD as a treatment against consumption. A respiratory illness later thought to be tuberculosis.

Paul Stamets (06:29):

And so we have a quarter of a mystery at hand because agarikon is duly active against DNA viruses, which has POCs and herpes and RNA viruses, which is flu As and flu Bs. And that's a conundrum because most of urologists would say, well, that's not right. And it may well be that this agarikon mushroom, for instance, it grows a hundred feet up in the trees oftentimes. So I have to find them on the trees have fallen down over the growing low or climb the trees with a friend of min. But as subject to a hundred mile an hour winds, hundreds of inches of rain per year. And yet this mushroom grows for up to 75 years under these adverse conditions. And this mushroom does not rot.

Steve Paulson (07:08):

Why is it so hardy?

Paul Stamets (07:09):

Oh, good question. I'm asking you the same question as well. And I think we can benefit from examples in nature and that's what we are on the path to discovery hopefully.

Steve Paulson (07:16):

You who have been talking about how you love doing your research and old growth forests. And you live in the state of Washington and you have brought into the studio a huge fungus or is it a mushroom? I guess I'm not exactly sure what the difference is there.

Paul Stamets (07:29):

So yes, this is a mushroom. Now, there's one to 2 million species of fungi. Estimated in the kingdom. 10% are mushroom forming fungi about 150,000 species, but we've only identified 14,000 species so far. So more than 90% of the species of mushrooms have not yet been identified. This one is a large wood conk.

Steve Paulson (07:46):

It's roughly what about a foot and a half long, maybe a foot high, sort of roughly the shape of an oversized football?

Paul Stamets (07:52):

Well, it looks to many people like a wasp nest or a beehive. And it has concentric rings of growth. And those are annual growth rings as hard like wood, in fact, a TSA broke my agarikon.

Steve Paulson (08:07):

As you were going through the airport.

Paul Stamets (08:08):

I was going through the airport and they wanted what was inside of it. I was horrified. It's a fungus. What's inside of it, more fungus. Right?

Steve Paulson (08:15):

So this is a particularly rare mushroom.

Paul Stamets (08:16):

This is one of the rarest mushrooms in the old growth forest. It's exclusive the old growth forest now thought to be extinct in Europe. The more that I study this mushroom, the more excited I am. And it's really, I think could go down in history as a medical breakthrough, as a resource for novel antibacterial and antiviral medicines together.

Steve Paulson (08:36):

Now there have been also been fungi use to help clean up toxic waste sites. Right?

Paul Stamets (08:41):

Yeah. That's micro remediation. That's something I've been actively involved in running these mycelial mats on wood chips, outdoors, downstream from factories and farms and the mycelial networks capture pollutants and they gobble them up.

Steve Paulson (08:56):

Wait, what did these mats look like?

Paul Stamets (08:58):

Everyone can see them today. Just go outside, find a piece of wood and just tip the piece of wood up. And you'll see underneath this white velvet find fibrous network called mycelium as analogous to the roots of an apple tree gives rise to the tree that gives an apple. Well, the roots are the mycelial network that is in all landscapes and under certain conditions it produces a fruit which is called mushrooms. The largest organism in the world is a mycelial mat in Eastern Oregon is 2200 acres in size 1,665 football fields.

Steve Paulson (09:32):

You're saying this is one single organism.

Paul Stamets (09:34):

One single organism. And it's one cell wall thick. When you see a dense on the ground, that can be more than eight miles of mycelium per cubic inch. This is the foundation of the food web. These are the interface organisms between life and death and they build soil.

Steve Paulson (09:49):

So what kinds of toxic substances then are sucked up by this mycelium?

Paul Stamets (09:53):

A whole Pantheon of compounds. These are grand molecular disassembler. We've been able to break down diesel spills, oil spills. Two of our fungi broke down VX soman and the sarin, which is a potent neurotoxin.

Steve Paulson (10:08):

So the trick in a sense to having a successful cleanup operation at a waste site, particularly a toxic waste site is to be able to break down those nasty substances. And you're saying fungi have particular properties that can do that.

Paul Stamets (10:19):

Indeed, a lot of the hydrocarbon based contaminants and even pesticides and herbicides, we actually can break them down with fungi. There's a mushroom called Turkey tail intermediates versa color that circumpolar all over the world, grows on wood and has an amazing property. It binds mercury even when it's dead, you can powder this mycelium up and you can throw it into mercuric ions in water and the mycelium hyper accumulate selenium and the selenium and the mercury come together as a biomolecular unit that makes it totally non-toxic.

Paul Stamets (10:48):

So the implications are enormous. These fungi offer a platform of solutions on multiple levels, and this is what's so exciting about them, but this is what nature is all about. Nature speaks to us all the time. We just need to listen.

Steve Paulson (11:01):

So here you are telling us that mushrooms can in some ways help save the world. And yet my guess is that the vast majority of scientists kind of take mushrooms for granted or they don't really think about it very much. So why are you out there when so few other people are touting the great benefits of these things?

Paul Stamets (11:18):

Well, I'm in great despair that something so important is so under evaluated, understudied, underfunded, and not given the priority that it should be. I like to say that the mycology departments should be as well-funded as the computer science departments. It is that important for the survival of life on this planet. And it speaks to that a little bit to what we call micophobia, the irrational fear of fungi.

Steve Paulson (11:40):

Well, wait for one thing, we've heard that some of them are poisonous.

Paul Stamets (11:43):

If a person dies from mushroom poisoning in the United States virtually every news media will pick it up. Very few people do die from mushroom poisoning. Very few mushrooms comparatively are poisonous. Of course, you should know what mushrooms are edible or poisonous before you ingest them just like any plants. Thankfully, we're a pluralistic society and we've benefited from Polish people and Europeans and the Japanese and Koreans and the Chinese. They're very mycophilic societies. The Chinese look at, for instance, the cordyceps mushroom that comes from insects as rebirth. It's a whole different psychology of looking at nature.

Paul Stamets (12:17):

And this is Earl Gore and Eel Wilson and other people have spoke to this, but we are really in a serious trouble. It is far more serious than I think anyone fully realizes we are in a massive extinction event and E. O. Wilson predicts that 50% of the known species to become extinct the next a hundred years. What happens when we lose biodiversity in micro diversity, it's like losing rivets of an airplane at some point we'll undergo catastrophic failure.

Paul Stamets (12:43):

Now we are evolutionary successes today. Yeah hoo, we made it so far, but for how long, and I've often thought if there was a United organization of organisms otherwise called, OO, would we be voted on the planet or off the planet? I think that vote's happening right now. And unless we get our act together and join with nature, we are could be happy to be a victim of the extinction event that we're creating.

Anne Strainchamps (13:09):

That's my mycologist, Paul Stamets talking with Steve Paulson. Paul is a researcher and writer. He's filed 22 patents for mushroom related technologies. He also runs a business called Fungi Perfecti. So as you've guessed, we're talking about the wonders of mushrooms today. And I have to say there is something both charming and also slightly weird about the level of devotion that mushrooms seem to inspire. It's like this really intense fan club or cult. I mean, there are people all over this country who will go to all kinds of extremes for a single mushroom.

Speaker 2 (14:08):

Just last fall here in New York. We had a really great year for maitake grifola frondosa, which grow under mature oak. And we were having a fantastic time just looking up the names of cemeteries that had oak in the name. So let me go drive up to the cemetery and collect the mushrooms that are growing under the trees. And so on the way back from one of these cemetery hunts in the fall, I saw this really big maitake growing underneath a tree in somebody's front yard. This is in Long Island and my husband and I were like, should we just grab it? No, no, we can't. This is wrong.

Speaker 2 (14:50):

So after much, like walking back and forth in front of this poor person's house, I finally knocked on the door and he was like, I was wondering what you're doing back there. We said, is it okay if we take the mushroom, I'll give you half of it. And he said, no, get rid of it. I don't want it.

Anne Strainchamps (15:11):

How big was that mushroom?

Speaker 2 (15:13):

Probably about 14 pounds.

Anne Strainchamps (15:15):

Wow.

Speaker 2 (15:16):

It was a really big mushroom. We could see it from the road. And they can grow to be tremendous. And this one was tremendous.

Anne Strainchamps (15:28):

Meet the mushroom hunters next. I'm Anne Strainchamps. It's To The Best Of Our Knowledge from Wisconsin Public Radio and PRX. How far would you go for a mushroom when you can find them at the grocery store, but you could also start picking your own maybe in secret wild places. You wouldn't tell even your closest friends about. Then you could start hanging out at mushroom festivals where you can drink mushroom beer and sing mushroom songs with other mushroom fans.

Anne Strainchamps (16:07):

At that point, you might start organizing your travel around mushrooms. Seasons. Well, Eugenia Bone does all of that. She's a food writer and a self-described mycophiliac. Shannon Henry Kleiber caught up with her the day before he had another mushroom expedition. This one to the Sierra mountains, to hunt for morels after a wildfire with a very big duffel bag.

Eugenia Bone (16:32):

So morels certain kinds of Morales grow in copious amounts after a fire. So the fire happens in the summer. And if there's enough rain in the spring in certain habitats these morels come up in huge numbers. And for the last, well, quite a few years, I've been going out to hunt whatever burns I could find. And so the Sierras have been happening burning for the last few years. So I fly out and I use my miles. I go on out there, I ran a car with knobby wheels and we take off into the Sierras and I bring home very large amounts of morels.

Eugenia Bone (17:09):

I will probably bring 15 pounds of morels back that are fresh and then more than are dry. So yeah, I'll have a duffle full of mushrooms. We pick a lot of mushrooms and it's super fun. Morels, by the way, I think they're like 200 bucks a pound. That's what you'd pay. So you can do the math.

Shannon Henry Kleiber (17:34):

Wow. Are they your favorite? Do you have a favorite?

Eugenia Bone (17:38):

I have a sort of top three or four. I love gypsy mushrooms. I love morels. I love porcini mushrooms. The boletus mushrooms. I love Chanterell. I love hedgehogs. I like all the wild ones the most, but the cultivated I'm not going to turn up my nose at a nice plate of sauteed champagne.

Shannon Henry Kleiber (18:00):

Oh, that sounds delicious. So tell me about the taste of some of those favorites. Take me through the taste because they all taste different from each other.

Eugenia Bone (18:08):

Well, to a degree. Right? Mushrooms are mushrooms. So they're-

Shannon Henry Kleiber (18:12):

They have umami. Right?

Eugenia Bone (18:13):

Yeah, exactly. This kind of meaty, savoriness. And that's thought to be the result of mushrooms contain a kind of pretty high grade protein. So that meaty savoriness is what you're tasting that high-grade protein. When you eat a mushroom, that's where the umami flavors thought to come from. One of the main differences, I think between say a, like let's look at maitake. Right? Which is the grifola frondosa. It's like this feathery mushroom. It looks like a little hand. You find them under oak trees in the wild, and you can find them in the supermarket too. They're cultivated.

Eugenia Bone (18:48):

So the wild ones taste up. It's like the difference between a domestic duck and a wild duck. The wild maitake are kind of cleanier. You taste more different soil type things. Soil and bark and leaves and worms. And they're more complex in a way. Whereas the cultivated maitake which are grown on a bag of oak chips, they don't have quite the complexity.

Eugenia Bone (19:12):

So that's a distinctive difference. Then the different tastes between the mushrooms summer more nutty, like the porcini, some are more perfumy or fruity like the chanterelle, the truffles are amazing. They're like pretty much always a combination of certain strong flavors like garlic and BO. So it was like the BO quality. And I think that's what's just so great. People always romance about truffle saying, ah, it's the you smell the wet leaves and I smell like BO and it's great.

Shannon Henry Kleiber (19:53):

And you love it.

Eugenia Bone (19:54):

I do. I do. And they're all like that. You've with truffles, I've gone truffle hunting in Oregon. They have other species. The black truffle is like a cross between a pineapple and a fart. It is just divine. And then there's another one, a little white one. That's really kind of great. That's like a garlicky armpit. I love that one.

Shannon Henry Kleiber (20:13):

Garlicky armpit. That's a great description. So to the very best kind of have that kind of dichotomy of like something amazing and something kind of awful and it makes the combination powerful.

Eugenia Bone (20:25):

That's what makes you love/lust it. It just turns people on. I mean, in the past boy, one time I remember I was at SOMA camp in California, that's Sonoma Mycological Association, and I picked a whole bunch of candy caps, which are great mushrooms. They have a flavor of maple syrup and they're so cool because that mapley taste, it gets into your bloodstream or something. But it's like, when you pee, it smells like maple. I mean, all of your sweat, everything sort of smells like maple, your sex smells like maple syrup. It's a very cool mushroom on a lot of levels.

Shannon Henry Kleiber (21:05):

That's great. Those are interesting. Where do you get candy cap mushrooms? Do you have to find those in the wild?

Eugenia Bone (21:11):

Yeah. There's camps and festivals all over the country, by the way.

Shannon Henry Kleiber (21:15):

So how do you love to cook mushrooms? I love sauteed in butter and onions and garlic and cheese and eggs. I'm just thinking of all the kinds of things I like to cook with mushrooms. What are your favorite ways to cook?

Eugenia Bone (21:29):

I cook mushrooms different ways. So the really exciting thing is you go out, you forge the mushrooms, you bring home a nice hall, and then what's the first thing you make. That's sort of my litmus test. So if I'm collecting the porcini, which we find in Colorado and the west Elks, and these are wonderful chubby mushrooms that we find them at 12,000 feet. Pretty high altitude and under conifer and the porcini, we slice on a mandolin into really, really thin slices. And then we slice Parmesan cheese from a hunk into really thin slices and then salt and olive oil. And we eat them raw.

Shannon Henry Kleiber (22:11):

Oh, that sounds delicious.

Eugenia Bone (22:13):

There's not a whole lot of mushrooms that are ideal to eat raw, but these like morels, if you eat a morel raw, you'll probably get sick from it because morels have to be cooked. But the porcini is fantastic raw. If I get a big load of morels, like the first thing I'll do when I get home after the red eye, after I collect these mushrooms in the Sierras then I take the red I home with all of my mushrooms in my suitcase. I'll do one of my favorite dishes which is in a Dutch oven. I put in a cut-up chicken and a stick of butter and a bottle of dry Sherry and as many morels as I feel like I can part with at that meal. And I cook it all together and then finish with a little cream and chopped tarragon and black pepper. And it's very luscious and very, I don't know, French, I guess. It's just divine.

Shannon Henry Kleiber (23:11):

So obviously some mushrooms are dangerous. They could kill us. They could make us very sick. How can you tell the difference and have you had a close call?

Eugenia Bone (23:22):

I always have thought it's a good idea to try to learn the ones that are poisonous with as much interest in vigorous than the ones that are edible. There's not so many poisonous ones. I mean, there's not so many that are going to take your liver out right in 36 hours but there's a few and learning to identify them. It's just learning how to identify you're not going to go into the woods and just eat like some Berry on a Bush. Right? You're going to know which you learn, which ones are edible and which ones are poisonous. So it's just a kind of learning curve. But then there's like all these mushrooms it's a spectrum. Right? So there's some that kill you. And then there's some that are really delicious like truffles and then there's everything in between.

Eugenia Bone (24:06):

So a typical example would be those mushrooms that we eat that are considered poisonous but we eat willingly like intoxicating mushrooms or mushrooms that some people eat willingly. Or for example, the amanita muscaria, the red mushroom with the white dots. So most of the time people think, oh, that's a poisonous mushroom. But my dad told me this story about how there's this fellow, Nick Mostro Pietro. He lived in Yonkers and he had a Christmas tree farm. And dad was visiting Nick at the Christmas tree farm. And they were walking around and Nick points to the amanita muscaria and the red mushroom with the white dots on it that's growing underneath the Christmas trees. And Nick said, oh, that's a good mushroom and my dad said, are you kidding? That's a poisonous mushroom.

Eugenia Bone (24:56):

And Nick said, no, no, it's really good. It's just that every time you eat it right afterwards, I fall right to sleep. And my dad's like, you're lucky to wake up. Well, it is in fact edible. I've eaten it before. So I ate, it was really great promptly right after ate it. I fell into this coma like sleep. I mean, it lasted three and a half hours or something. It was like the drug they give you when you have to have a colonoscopy. I mean, just completely out. And I woke up with one shoe on but it turns out that this is a mushroom in this capacity that's used with one tribe anyway, the Evan tribe in Siberia, and then the mushroom is prepared and used as a sleep aid for elderly people. So when we talk about poisonous mushrooms it's a spectrum.

Shannon Henry Kleiber (25:52):

So was it a good sleep.

Eugenia Bone (25:56):

It was a complete and total unconsciousness.

Shannon Henry Kleiber (26:03):

Do you think that in studying mushrooms, there's something we can learn more about ourselves as humans?

Eugenia Bone (26:10):

For me, I would say, yeah, I think there's a lot. But what is most meaningful to me was the realization that what I thought was the world was really limited by my perspective, and that when I started to get into mushrooms, I realized that there was a lot more to nature than I could see from where I was standing. And I had to take that extra step to start learning about it. Because fungi is an interesting, they sort of bridge the unseen and seen world. They are microscopic with macroscopic parts in the mushrooms. In a way like fungi are like a gateway drug to microbiology, which is this huge subject of great import to the workings of our planet. Just damn, it's exciting.

Anne Strainchamps (27:16):

Eugenia Bone is a food and nature writer. She's the author of Mycophilia and Microbia, and she's a former president of the New York Mycological Society. Shannon Henry Kleiber talked with her. So mushrooms have inspired scientists and chefs and my mycologist Lawrence Millman says they have also inspired a few composers.

Lawrence Millman (27:45):

Russell Hallock was a Czech individual of extreme eccentricities who would go into the forest with a notepad and write down the songs that mushrooms were singing. He composed, I think it was about 1500 mushroom songs. Now he was indeed a mycologist, so he could identify different species and the different species had different songs. And he said that he sometimes could identify the species from a distance by the song he heard him singing.

Lawrence Millman (28:41):

I have not decided whether this is an archetypal example of Eastern European humor or some form of synesthesia of i.e. the music and the eyes somehow combine. He was both a serious musician and a serious mycologist. He composed what's called a Mycol Symphony, mushroom symphony, where he takes all the mushrooms in the forest and combines them into work. And it's rather obvious that he's heard Bayla bar talks to singing too.

Anne Strainchamps (29:34):

So then there's another composer, John cage.

Lawrence Millman (29:37):

John cage. Yes.

John Cage (29:39):

You know that I have been selling wild mushrooms.

Lawrence Millman (29:43):

The American John Cage composer is maybe the wrong word. He was a performance artist who white to amuse people and take them out of their boxes. However, he was also mycologist. He helped restart the New York Mycological Association. His interest in fungi was primarily in edibles, but he wrote these odd poems and books that are sort of throvian about his appreciation of nature.

John Cage (30:20):

I was sure that there was a high cue poem that would have to do with mushrooms.

Lawrence Millman (30:28):

In one of his works he talks about this fly agaric. I mean, isn't scarier. It's not deadly poisonous.

Anne Strainchamps (30:37):

Is it hallucinogenic?

Lawrence Millman (30:38):

Yes. But it also can result in a trip to the restroom, in fact, numerous trips because it opens the seams at both ends so to speak.

John Cage (30:53):

That's unknown brings mushrooms and me together.

Lawrence Millman (30:59):

But he said that if you played a Beethoven quartet for this mushroom, it will become edible.

Anne Strainchamps (31:11):

Did he make any music inspired by mushrooms?

Lawrence Millman (31:14):

Yes. He wrote some songs about collecting mushrooms. He didn't listen to mushrooms and then record their music but he was inspired by looking at them. Definitely inspired by looking at them.

Anne Strainchamps (31:36):

Lawrence Millman tells a lot more stories about mushrooms in his new book Fungipedia. Okay, we've given you lots of perfectly good, rational reasons to love mushrooms. Now, let's go down the rabbit hole to full on mushroom consciousness.

Speaker 10 (31:57):

By the way, I have a few more [inaudible 00:31:59]. One side will make you grow taller.

Speaker 11 (32:03):

One side it floats.

Speaker 10 (32:04):

And the other side will make you grow shorter.

Speaker 11 (32:07):

The other side is what?

Speaker 10 (32:10):

[inaudible 00:32:10] of course.

Anne Strainchamps (32:12):

Coming up. I am Anne Strainchamps. This is To The Best Of Our Knowledge from Wisconsin Public Radio and PRX. So there are mushrooms and then there are mushrooms. Magic kind.

mMichael Pollan (32:34):

For me, this experience was all about nature.

Anne Strainchamps (32:39):

This is Michael Pollan.

mMichael Pollan (32:42):

I was in my garden in New England. And I had an experience of the plants that I'd never had before. It was a humid August day and the air was palpable. It was thick and there were these dragonflies, huge amount of dragonflies traffic to this day, I don't know how much of it was real and how much of it I imagined. It was the end of the day and the pollinators were getting their last licks in and the plants were going me, me, me. Come pollinate me.

mMichael Pollan (33:12):

And they were talking to the bees, but they were talking to me too. They're returning my gaze. All these leaves. It was like, oh my God, they really are cautious. Everything was alive. And I know how crazy the sounds. I know that plants aren't really conscious in the sense we mean it. So there mysteries abide.

Anne Strainchamps (33:38):

Michael Pollan is a journalist who's written extensively about food and plants. And most recently about psychedelics and a book called How to Change Your Mind. His experiences led him to join the ranks of ethnobotanists, neuroscientists and others who are trying to unlock the secrets of psychedelic mushrooms. Not in order to have more or better trips but because they suspect that mushrooms might help answer some of the big questions, like the origins of our evolution, the development of human consciousness. And there's also this totally bizarre idea. The stoned ape theory. Steve Paulson has the story.

Steve Paulson (34:20):

The first thing to know is that magic mushrooms go way back in human history.

mMichael Pollan (34:27):

Probably millennia. I mean, the first reports we have this isn't a written culture but when the conquistadors get to Central America, they find people using mushrooms in their religious ceremonies as a sacrament. And they called it Teonanácatl which has meant flesh of the gods. That's of course, what the Christians called their sacrament too. Right?

Steve Paulson (34:51):

Right.

mMichael Pollan (34:51):

It was the flesh of God that you're eating in the communion. So this was very threatening to the Catholic church because here was a sacrament that actually really worked. I mean, you didn't need faith to see God you met God.

Steve Paulson (35:04):

Or is the ethnobotanist Dennis McKenna.

Dennis Mckenna (35:07):

It carries a much bigger kick than the Catholic Eucharist. So Catholicism and Christianity, brutally suppressed all of these shamonic practices. They were particularly brutal with the mushrooms.

Steve Paulson (35:23):

And they crushed it.

mMichael Pollan (35:26):

They absolutely banned it. They destroyed mushroom stones. They tortured people who practiced it.

Steve Paulson (35:33):

Mushroom stones. So they're actually Like little statues in the shape of mushrooms.

mMichael Pollan (35:38):

Little statues, and some of them pretty big but they are stones carved in the shape of mushrooms. There've been many theories about what they're for. They're found all over Guatemala and Southern Mexico.

Dennis Mckenna (35:49):

Some of these miniature mushrooms stones in Guatemala, they go back to 3000 BC. Which is pretty far back.

mMichael Pollan (35:58):

And now they'd turn up in farmer's fields occasionally because people buried them. They were afraid to be caught with them. So the mushroom cults, as they were called, and of course we call it religion, a cult, when we don't like it went underground and was thought to have disappeared until the middle of the 20th century.

Steve Paulson (36:20):

So mushrooms largely disappeared from public view and psychedelics had gone underground, but then the Swiss chemist, Albert Hoffman accidentally stumbled onto LSD and rumors started swirling around that the mushroom was still used in sacred ceremonies in Mexico. And that's when magic mushrooms came roaring back. Thanks to one man Gordon Wasson that's right. Who would seem to be the most unlikely person to turn psychedelic mushrooms into a mainstream phenomenon? I mean, he was a vice president-

mMichael Pollan (36:54):

He was a banker.

Steve Paulson (36:55):

at JP Morgan.

mMichael Pollan (36:56):

He was very plugged in New York. He marries a Russian woman, a pediatrician, and she liked many Russians is a passionate mycophile. He like many Americans and people of English extraction was a mycophobe, fearful of mushrooms. Anyway, the story goes that on their honeymoon, they went up to the Catskills and they're walking in the woods and she starts finding all these mushrooms and she starts collecting them in her skirt and makes this big pile of mushrooms. And she proposes to cook them for dinner. He absolutely refuses to eat them. She eats them. He thinks he's going to wake up a widower the next morning. But lo and behold, she knew what she was doing. And this got him very interested in mushrooms.

Steve Paulson (37:41):

So in his spare time, Wasson developed a lifelong obsession with mushrooms especially the psychedelic ones. He studied how they influenced human cultures around the world and came up with a theory that the origin of religion was actually rooted in people's transcendent experiences on magic mushrooms.

mMichael Pollan (37:59):

And if you think about it, where do these interesting, bizarre ideas at the heart of many religions come from that there is a beyond that there's an unseen world. That there is a realm of the dead that you could visit. That there is a heaven and hell. I mean, these are interesting ideas and you could see why having a psychedelic journey would convince you of their truth. He looked into the use of amanita muscaria in Siberia. I think it is. And the Eleusinian mysteries of the ancient Greeks, where they all got together once a year. And they had a rite around Demeter, worship of Demeter. And everybody partook of this potion called the Kykeon, which has also never been really identified, gave people access to an unseen world.

mMichael Pollan (38:48):

And they went and visited their ancestors. And he believed that two might've been a derivative of the ergot fungus. That is the fungus from which LSD is derived. But then the last case in the most relevant, he heard about these mushroom cults in Central America. And he went looking in Mexico-

Steve Paulson (39:09):

For years. Didn't he? Multiple trips down there.

mMichael Pollan (39:12):

He had like 11 trips down there for-

Steve Paulson (39:14):

Looking for someone who would take him in so he could participate in a mushroom ceremony.

mMichael Pollan (39:18):

Yeah. And given the secrecy that surrounded it, earning someone's trust. So they would actually say, yes, we do use mushrooms this way. And yes, I will administer some to you but he finds a woman a curandera or healer named Maria Sabina in the town of Huautla de Jiménez, which is a couple of days by mule, outside of Wahaca in the very remote mountains. And she gives him the mushrooms, what she calls the little children. And he has this experience in the basement of this house. And he brings a photographer and he recounts this experience in the pages of Life Magazine in a like 17 page article.

mMichael Pollan (39:59):

The reason he gets it into Life Magazine is that he's friendly with Henry Luce.

Steve Paulson (40:04):

The publisher.

mMichael Pollan (40:05):

And Henry Luce, as it turns out is a giant fan of psychedelics. He's had psychedelic therapy. I know it's the weirdest history.

Steve Paulson (40:13):

It's absolutely fascinating.

mMichael Pollan (40:15):

But you have to remember all this is illegal. Right? This is 1955. He has his experience in 56 or 57. He publishes the article and this article really introduces much of the west to psychedelic mushrooms and psychedelic experience in general. So Gordon Wasson is really a pivotal figure in this history.

Steve Paulson (40:38):

By the sixties. Psychedelics had become part of the counter-culture not only was there plenty of experimentation, scientists launched a series of innovative research projects on possible therapeutic uses.

Timothy Leary (40:50):

So I went to Mexico.

Steve Paulson (40:51):

Timothy Leary.

Timothy Leary (40:55):

To use mushrooms. Called secret mushrooms.

Steve Paulson (40:55):

Read Gordon Wasson story in Life Magazine. And once he became a Harvard professor, he ran various studies of both psilocybin and LSD. Often involving his own students, which got him kicked out it's from Harvard. And by the late sixties, the psychedelic revolution had imploded and the FDA shut down all the research. And this wasn't exactly like the Spanish crackdown down on mushroom cults. But once again. The sacred mushroom went underground. And it might've stayed that way if not for a few mushroom obsessives who kept stoking the flames.

Terence McKenna (41:39):

It is still absolutely mysterious, appalling, challenging boundaries. Desolving an unavoidably ecstatic. It is the living myth.

Steve Paulson (41:52):

Terence McKenna and ethnobotanist and legendary psychonaut and traveled all over the world, studying and experimenting with a whole range of hallucinogens. Even after they were banned, McKenna was one of the few people who still talked openly about mushrooms. And he came up with a wild idea that eating magic mushrooms led directly to the origins of human consciousness. Essentially, the mushroom made us human. This is known as the stoned ape theory.

Terence McKenna (42:24):

If we're looking for a missing link, it isn't a transitional skeleton. It isn't meddling by extra terrestrials. It has to do with the fact that we began to allow into our diet an exotic pseudo neuro-transmitter. And I believe that mushroom was the triggering factor that moved us from being an advanced hominids, an advanced animal to being in fact, a conscious self-reflecting, caring, thinking, dreaming, striving human being.

Steve Paulson (43:08):

This is true? I find it completely implausible. Okay. This is really far out the idea that magic mushrooms rewired the brains of our ancient ancestors and created human consciousness. But the funny thing is people can't stop talking about it. The Terence McKenna died nearly 20 years ago, but his younger brother, Dennis, who traveled with Terrence on some of their wild psychedelic adventures in south America and wrote two books with him, he has his own take on the stoned ape theory.

Dennis (43:47):

Actually, I came up with the idea. You wouldn't want to know. I came up with the idea, but he popularized it.

Steve Paulson (43:55):

His idea was psilocybin mushrooms enhanced visual acuity. They were useful for hunting. You take mushrooms and you could spot the game.

Dennis (44:07):

Yes, they do do that. This is where his theory of my theory differ. I say, one of the things that can happen often with psychedelics and especially with mushrooms is so-called synesthesia where you get crosstalk between sensory modalities. So you can see sounds. What I've said for a long time is that this is the key to language because language is synesthesia. It's a learned skill that mushrooms taught us. I can say a word table. Chances are you visualize a table in your head. Right?

Steve Paulson (44:48):

Right.

Dennis (44:48):

Mushrooms provided that key link between a meaningless sound, a potentially meaningless image and a meaningful interpretation. So mushrooms were the key to how we learn to create symbols.

Steve Paulson (45:07):

I have to back up for a moment just to see if I understand what you're saying. So you're saying that this ancient consumption of mushrooms, magic mushrooms, tens of thousands of years ago triggered something in the brains of our human ancestors that helped us be able to talk?

Dennis (45:24):

That helped us be able to talk. Yes, and actually helped us be able to develop a language. But it's not simply that we ate mushrooms and became smart. We do know from the fossil record that there was an enormous almost explosive expansion of the hominid brain over about 2 million years. It increased three times in size. Two million years is not very long in evolutionary terms. Something made this happen. These people evolved in complex environments with a lot of challenges. I think the mushrooms gave them the ability to visualize abstractions essentially to create models in their heads. They gave them imagination.

Steve Paulson (46:20):

So today, once again, psychedelics are back, not legally, at least yet, but in labs around the world, scientists are rediscovering their therapeutic uses. We are in a new golden age of psychedelic research. And Robin Carhart Harris is one of the leading experts. In his lab at London's Imperial college, he's been putting people on psilocybin into brain scanners in his groundbreaking studies of treatments for depression and anxiety. So what does he think of the stoned ape theory?

Robin Carhart Harris (46:55):

It's a fascinating idea, really exciting kind of spine chilling yet. I'm not sold. I just think that it's a bit too psychedelic centric and it's not clear that every human culture took psilocybe mushrooms.

Steve Paulson (47:12):

So it could be, we're asking the wrong question. Maybe this isn't really a matter of trying to prove that magic mushrooms jump-started the human brain long ago. Carhart Harris is more interested in figuring out why psychedelics have such powerful effects on the mind and what that might tell us about the nature of human consciousness. He says, these substances can open up new neural pathways and they actually give our brains access to more information. In fact, he calls psychedelics mind revealing rather than mind altering.

Robin Carhart Harris (47:43):

People have insights. Emotional insights, personal insights, remember things sometimes very remote into their childhood.

Steve Paulson (47:51):

Is this tapping into our unconscious?

Robin Carhart Harris (47:54):

Well, that's the implication. Yes.

Steve Paulson (47:57):

It suggests something pretty powerful, which is that we don't normally in our everyday waking state really don't have access to maybe what's most important in our minds. Maybe we need some help getting there.

Robin Carhart Harris (48:10):

Yes.And then it raises curious questions like why has the mind and the brain evolved that way.

Steve Paulson (48:16):

And the world is bigger is what you're saying. Are psychedelics more expansive?

Robin Carhart Harris (48:20):

Yeah, I suppose. Because so much of world is actually inner and it's so vast. That's the huge revelation I think that psychedelics bring is just that symbolism and the iconography that you'll see an art, for example, or that's depicted in horror films or in religions. It's all there in a very vivid and elaborate way that one can experience under a psychedelic.

Steve Paulson (48:53):

There's no question, a psychedelic experience can blow your mind. It can also be terrifying. And the thing about psychedelics that's different from any other drug, every person's experience is unique and unpredictable. And for most people unforgettable, remember Michael Pollan from earlier, he says his psychedelic experiences fundamentally changed him.

Michael Pollan (49:23):

The brain is more mysterious or my brain is more mysterious than I understood and my mind is. But I also was changed in my understanding of what it means to have a spiritual experience. Something I don't think I'd ever had. Something I was kind of allergic to. I tended to think that to be spiritual was to believe in the supernatural and I very much didn't then. I'm really a pretty staunch materialist in my outlook on things. But I found that what happened when my ego dissolved and that psilocybin experience, the walls come down and you merge with whatever is around you. And it made me understand that no, the real definition of spiritual is not something supernatural it's connection, spiritual experiences, deep, powerful undefended connection between the self and what is normally in other an object, whether it's another person, music, the universe, nature, the walls come down and you have this powerful sense of connection, which many people call love.

Anne Strainchamps (50:41):

To The Best of Our Knowledge is Produced at Wisconsin Public Radio. Our executive producer, Steve Paulson brought us today's mushroom episode. Joel Hartke is our sound designer and technical director. And they add help from Mark Riechers, Angelo Bautista, Shannon Henry Kleiber and Charles Monroe-Kane. I'm Anne Strainchamps. Thanks for listening.